It’ll likely come as no surprise that top racers are once again* cheating on Zwift. After all, cheating and cycling are as intertwined as peanut butter and jelly. And while historically cycling has seen cheating take the form of doping (or, motors), more recently that’s shifting into the digital realm as cyclists move indoors and compete there. Especially this year where outdoor racing is few and far between.

(*And by ‘once again’, I mean ‘still always’)

The last time there was a public kerfuffle with Zwift and cheating it was at their first indoor championship – broadcast live to millions of households around the UK (and beyond). A big production set and the whole bit. Only to find out later that the winner, Cam Jeffers, obtained the faster winning bike by using a bot to accumulate fake mileage. While some defended the rider’s actions due to the semi-muddy circumstances around it, that’s a much harder stance to take this time around.

But this time around, as first reported by Caley Fretz on CyclingTips, Zwift has banned two racers from future races for a period of six months each. Though, the incidents happened a month apart.

More notable though in this case is that Zwift clearly sought to throw down the virtual gauntlet with data that overwhelmingly shows the two women in question were falsifying files. But in my mind – that almost escapes the bigger issue as you’ll see: Why on earth does Zwift even allow this sort of pathway anyway?

And why exactly are these decisions being announced today specifically, versus when they actually happened? No worries, I’ll (try) and explain both the technical and non-technical bits. Hold onto your saddle.

It’s About the Coverup, not the Crime:

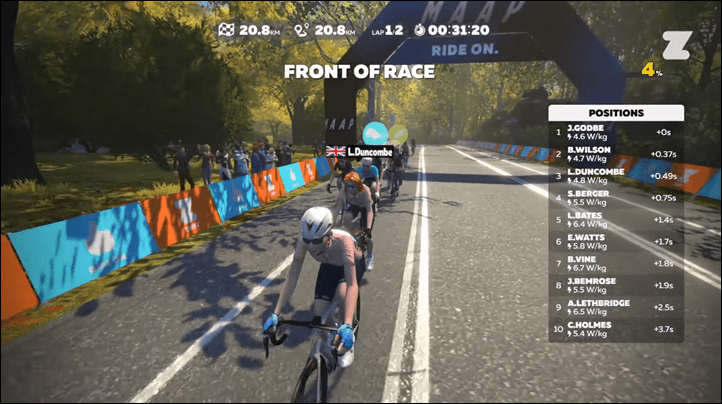

There’s two events in question here – both of them were 12 years ago by 2020 standards. The first was on August 17th, where Shanni Berger was competing in the ‘Off the MAAP’ series, specifically Race #2. You can watch that full race here. She had provisionally finished 2nd in that race. According to Zwift’s Performance Verification Board, this was case #80 (yes, there were 80 cases by this point, more on that later in this post).

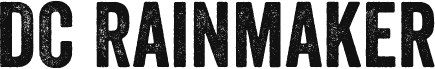

The second event in question is on September 17th, 2020. This was an event where Lizi Duncombe was racing the Zwift Racing League – Women’s Qualifier #2. She provisionally finished 4th. According to Zwift’s Performance Verification Board, this was case #109.

One of the things that’s important to understand is that for certain levels of Zwift racing, there’s a slew of requirements. These include allowances on what types of gear/trainers they’re allowed to use, and how they must verify the results. Some of the requirements are merely window dressing. For example, Zwift allows certain types of trainers that are known to be inaccurate while disallowing others. Zwift themselves don’t do any actual true certification of trainers’ accuracy (else, they’d ban more trainers). In any case, at a high level, the following core things are required (the actual list is much longer, in the full ruleset listed):

A) During the race, riders must also record a secondary power source to another device (a Garmin/Wahoo/etc…), in addition to the trainer. Meaning, they need a power meter and must record another file. [2.7.1]

B) Riders are to submit a pre-race weigh-in video per a set instructions [Appendix A: Pre-Race information]

C) Riders are to submit a video recording of riding a specific Zwift test course [Appendix A: Pre-Race information]

D) Riders need to submit the exact model, firmware, serial number, and calibration information of their trainer and power meter prior to the ride, as well as photos of that. [Appendix A: Pre-Race information]

E) Riders need to submit an outdoor ride file on a gradient of 5% or more from the the last 12 months, with 5s/1m/5m/20min efforts. [Appendix A: Pre-Race information]

F) Riders need to submit calibration and spin-down video evidence for both the smart trainer and power meter [Appendix A: Pre-Race information]

G) Riders need to do the hokey pokey, recorded on video. [Appendix Z: Squirrel Section]

However, it’s this first one we’re gonna focus on today – 2.7.1 – the dual-recording of the race files. Riders are required to submit that secondary recording file to Zwift shortly after the event. In the case of Lizi Duncombe, she had a file from her warm-up, but didn’t have anything beyond that. Zwift assumed this was a mistake and reached out to the rider:

“The Board judged that this may have just been an inadvertent mistake by the rider, but nonetheless without an independent recording of the rider’s efforts it was not possible to verify their performance in the race and their result was therefore annulled. 2. Shortly after the rider submitted their first dual-recording file to ZADA, they uploaded a different dual recording FIT file to ZwiftPower. This second new file showed a dual-recording of the race labelled as coming from the rider’s Garmin and of their Assioma pedal based power meter.”

However, Zwift’s performance board then went on to crucify the file she sent in, noting (quoted sections are their words):

1) The rider had claimed the file was from an Edge 820, however clearly wasn’t, according to Zwift: “contained a “Version ID” label of “562”. This number is given to FIT files produced by Zwift. FIT files produced by a Garmin Edge 820 use a value of “1250”, and examination of multiple other dual-recording files from the rider from different races show they all contain values of “1250”.

2) Next, it noted that the file’s device timestamp (different than the date of the workout) was inconsistent: “It contained a “Device Timestamp” label of “6th Jan 2015 14:08”. This value is given to FIT files produced by Zwift. FIT files produced by a Garmin Edge 820 use a value of the time of the recording, and examination of multiple other dual-recording files from the rider from different races show they all contain values of the current time of the recording.”

3) The file had GPS coordinates in it. It shouldn’t have: “It contained GPS co-ordinates for the ride. This would be expected for a Zwift generated FIT file, but a Garmin recording a pedal based power meter would have no knowledge of the location in Zwift of the rider’s virtual avatar and would therefore be impossible for it to produce.”

4) The file was too perfect: “The power values contained in the file were all different from the Zwift recorded FIT file by the same percentage. For example, at every point in time when the Zwift recording recorded a value of 297 Watts, the second FIT file sent by the rider showed exactly 294 Watts. The correlation between the power recorded by Zwift from the trainer, and the power recorded by the Garmin from the pedals was mathematically perfect (i.e. Correlation Co-efficient: R=1.00). In any real-life scenario, for the trainer and power meter to be perfectly correlated across every single data point from rest to maximal sprint power, is impossible.”

So in a nutshell, she or someone on her behalf, tried to edit the original Zwift .FIT file, tweak the values by 1% across the board, and then call it a different power meter. Except, they didn’t understand enough about the nuances of this to make this even remotely passable. Thus, she was voted off the island Watopia for 6 months.

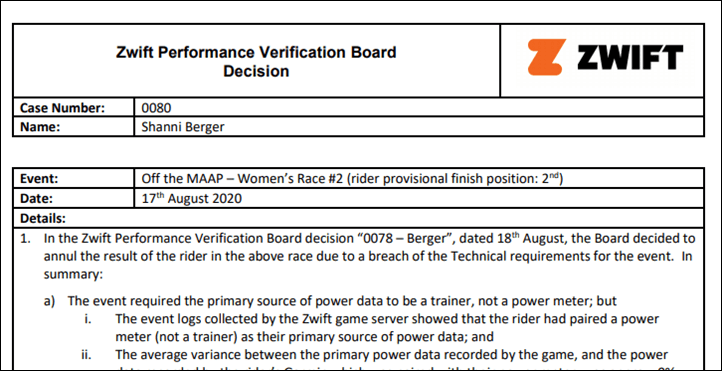

Next, we’ve got Shanni Berger’s violation. Her downfall was also falsification of files, but not actually in the same way. In her case, the event she participated in required that the trainer be a power source, not a power meter. While she had a Saris controllable trainer paired, she instead used a Stages power meter as the power source. This was likely just an innocent mistake. I’ve done the same thing too, not realizing it.

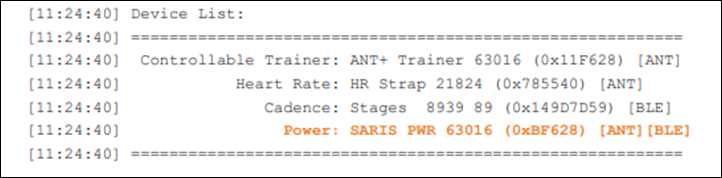

You can see in the below screenshot from Zwift that the trainer was paired as a controllable trainer, then the power source listed as the Stages power meter for both power and cadence source. This is from the files sent quietly behind the scenes to Zwift.

Having two different sources is something that likely thousands of Zwifters do every day without even thinking about it. And frankly, depending on the type of trainer and exact Stages model involved here – her decision would probably have been more accurate. For example, if she had a wheel-on Stages M2 trainer, then I’d defer to the accuracy of the Stages power meter (inversely, if she was on a Saris H3, I’d trust that over a Stages left-only unit). We don’t know the exact model of the trainer or power meters, it wasn’t specified.

However, that’s also not what matters here. The rules for that race stated a trainer had to be used as the power source (don’t worry, more on this later).

So, Zwift DQ’d her after the fact, based simply on that. This happens daily. It’s not a big deal, it’s not even the equivalent of getting a parking ticket. However, what happened after that though is the big deal.

According to Zwift and the full write-up about the incident, the company:

“received multiple emails from the rider’s Team Manager and team owner, protesting the annulment of the result. Their stated grounds for this were:

a) That the rider had been “adamant” that they had their trainer paired as the primary power source.

b) That the rider had provided the team with the Zwift log.txt file recorded on their own computer from the event which included the following section identifying the pairing used by the game (emphasis added):

Here’s the data snippet they included in those logs they sent, note the highlighted orange part. Also – I appreciate that Zwift chose to highlight the files in company orange, rather than any of the millions of colors available. Never in my IT career have I seen someone use orange as a text highlight choice. Kudos on keeping the brand on-point:

At the juncture above, they (her, her team, whomever) – had already screwed up. See, a power source can’t be paired in Zwift at the same time on both ANT and BLE. It’s physically not possible. And that’s where Zwift starts to throw down their technical gauntlet again:

“Expert evidence received from the Zwift software development team shows that the Zwift game does not produce log files in this format. Paired devices are either listed as being connected via “[ANT]” or “[BLE]” but never both.”

Then they go onto iterate one by one through a litany of issues with the modified log file (albeit, seemingly unable to know that power meter is two words, not one):

“The sections of the riders log.txt file that correspond to the game detecting the riders powermeter are all missing from the file. Whilst this might be possible if the rider had no powermeter, the rider freely admitted that they were using a power meter as a cadence sensor (and the riders log.txt file also confirms the use of the powermeter as a cadence sensor during the event). If the rider, and the riders file, are therefore to be believed as accurate, then the game would have to be using the powermeter as a cadence sensor, without ever having detected its existence.”

And again, where line items in the log file reference a difference between the two sources was left in:

“In total there are 27 lines in the riders log.txt file that differ from the original version – all of them relate to the powermeter; either lines that are completely missing in the riders version, or differ by referring to the primary power source as being the trainer rather than the power meter. However, not all of the lines referencing what the primary power source is are different. In the riders log.txt file there are still some lines that state that the primary power source is the riders powermeter. If the rider, and the riders file, are therefore to be believed as accurate, the game would have to be rapidly and repeatedly swapping between using the trainer and powermeter as the primary power source (and, as point (4b) above, without having ever detected the existence of the powermeter).”

Wait, there’s more. Here where they explain that while the rider/team changed all the references to the word ‘Stages’, in reality, Zwift actually uses ID’s behind the scenes, and these weren’t correctly swapped out.

“As noted in point 4c above, the lines in the riders log.txt file that differ all relate to the riders powermeter. Explicitly though, they all refer to the name of the power meter (i.e. lines that use the word “Stages”). However, the log.txt file also logs out internal game-specific numeric codes for all the equipment being used as well as human readable words. Notably, these game-specific numeric codes for the equipment being used that are in the two files are identical between the riders version of the log.txt file and the original version. This clearly indicates that the game is using the riders powermeter as the primary power source, and if the rider is to be believed, the game must have, for some unknown reason, chosen to change just the human readable names it gives to the equipment.”

Then Zwift tried to see if the rider was being aided (or tricked) by their team, and asked for the original files directly from the rider, rather than the team that had sent them:

“As noted above, the Log.txt file containing the discrepancies outlined above was passed to by Zwift by the riders team, and it was unclear whether these changes were present on the file stored on the riders computer, or had been made afterwards by their team. To help establish this, the rider was requested to send the files stored on their computer directly to Zwift. The files they sent were identical to those sent to Zwift by the team (i.e. contained the different primary power source, and incorrectly formatted data).”

So in other words, the rider didn’t throw the team under the bus, and just passed along the fake data file again (from the team), as opposed to her actual original data file.

Eventually, the rider admitted something:

“After numerous exchanges, Zwift received an email from the rider expressing their “apologies for any misunderstanding” and that it’s “very possible that I [the rider] made mistakes with the software due to human error”.

It’s not clear from that whether she’s admitting to simply selecting the wrong power source (a relative non-issue and frequent thing), or admitting to faking the data with her team (very much an issue).

Ultimately though, in both cases – had the riders simply accepted the DQ’s due to pressing the wrong buttons in the software, or forgetting to start their Garmin’s, this never would have been an issue. Neither Zwift nor anyone else is saying these riders cheated during the race. But rather, that they willfully “fabricated” and modified the data after the fact to avoid a DQ. As is often the case in mistakes, the coverup is far bigger than the crime (or, not even a crime at all originally).

Wait, why now?

So my first question about reading this was more simplistic: Why was this being just announced now?

After all, these events occurred exactly three months and two months ago, with the final Verification Board Decision occurring within 3-4 weeks – way back in September in the first case.

Well, the definition of ‘now’ is probably important here. After all, nobody knew about this in public until Caley’s article. According to Zwift though, Caley was in turn tipped off to the details by someone in the Zwift community (probably another racer). But also according to Zwift, the details of these have apparently been published for a while.

I can’t seem to find the exact date yet they appeared, but it was sometime this November. Zwift says that they were there sitting on an esports rules page that’s virtually impossible to find unless you know the secret handshake. But that almost immediately brought me to the next question: As of September there were 109 cases, what happened in the other 107 cases (plus how many more between now and then)? Why were these two riders being made a clear scapegoat?

Zwift said that basically those Performance Verification Board decisions cover a broad range of things, including cases where trainers or power meters are simply inaccurate enough to invalidate a rider’s race. Plus, in some cases the person was found totally innocent of any issue at all (such as being able to prove their data was correct). So ok…that removes a pile of them. But then what about people truly guilty? After all, I have a hard time believing that after 109 cases only two people are guilty.

Well, the company says that they’ve been internally trying to find the right line there for what to publish or not publish. At one extreme you’d publish everything, guilty or innocent of purposeful cheating. That’d be for everyone – random dad in their garage doing a community race at 5AM on a Tuesday, or WorldTour Team pro cyclist doing the Virtual Tour de France ride. All the same in that scenario.

While at the other end you’ve got only publishing guilty-type verdicts for pro racers on pro events of ‘value’, where a prize is being handed out, and where the riders are already held to a higher standard.

And that’s ultimately what Zwift has settled on. At present they aren’t publishing details of regular users doing bad things. That fart just goes away quietly into the night. It’s only the pro riders during races “of value” that will get nailed publicly.

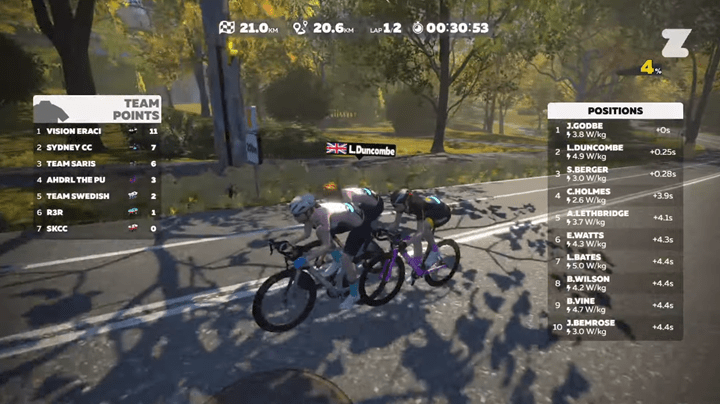

(Fun screenshot tidbit for those eagle-eyed Zwifters and readers, despite the actual races where these riders were banned taking place a month apart in different race series, the two riders actually competed head to head and even in the same frame in the initial Aug 17th Off the MAAP race where Shanni Berger was DQ’d. You can see this in the video here, or just the screenshot above. It wouldn’t be for another month until Lizi Duncombe ran afoul of the rules and got her DQ.)

Zwift Needs to Improve:

It’s easy to blame these two riders. And yes – they deserve 100% of the blame they get here. But it’s important to point out that both of these bans were more for the coverup than the actual crime. In both cases, the riders would have simply been DQ’d due to the technicality of not having a secondary recording file for that event. There’s a million reasons that can occur – none of them nefarious (what was nefarious here was poorly creating a fake file to cover up the fact, attempting to avoid a DQ).

To put it in perspective, as one whose job is to create secondary recordings of power meter data – just last night I went for a ride, and two out of the four units I had recording failed in some way. One was a watch that wouldn’t start recording due to a bug (not my fault), and the other was a head unit I accidentally pressed pause on mid-ride during a swipe and didn’t realize it till later – basically invalidating that recording (totally my fault). Obviously, I wasn’t racing, but my point is that what these two riders did during the race wasn’t really a big deal in the grand scheme of things, it was effectively just missing paperwork. It’s what they did afterwards that got them in trouble (faking the paperwork and lying about it).

However, this ultimately brings up the most obvious of questions: Why on earth do athletes need to go through this trouble to have a secondary power source recording?

Seriously, why? So, I asked.

Zwift says that “it’s something that is challenging to implement but could be done and has been discussed. However, as mentioned, it boils down to prioritization at this time, and while dual power recording in-game would be valuable to one cohort, it would stop us developing another area which we currently feel would be of value to a greater number of Zwifters.”

Which basically sounds like every other response Zwift gives on why bugs or long outstanding issues aren’t resolved yet.

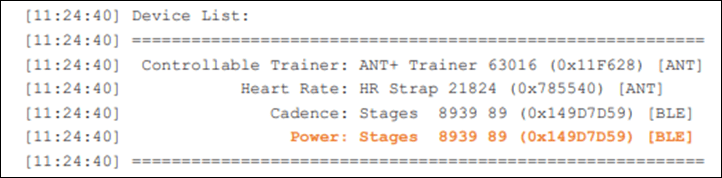

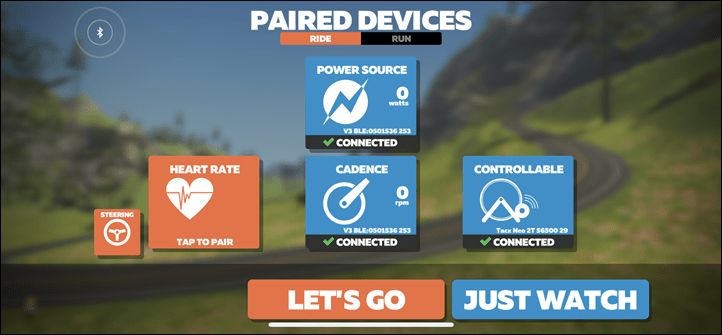

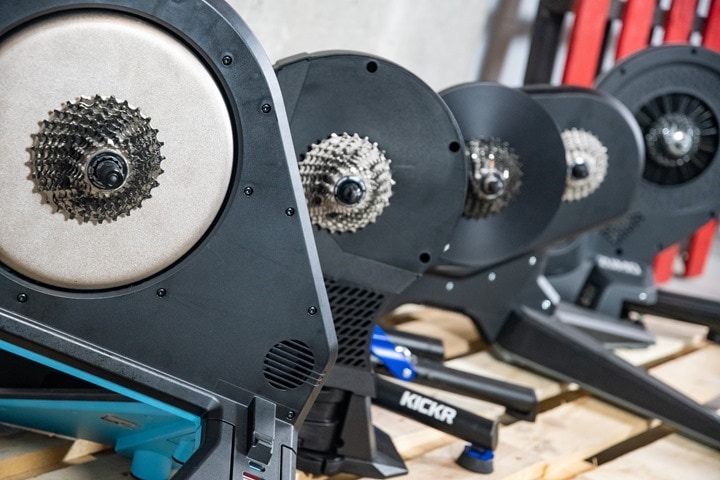

Zwift already pairs to multiple sensors as part of the pairing menu – why on earth doesn’t it just record those dual sensors and then upload them to Zwift? You can see the pairing data below, using an example of having a trainer connected and a different power source (notice the controllable trainer is listed as the Tacx NEO 2T, while the power source is listed as the Vector 3 pedals – V3 BLE):

While I try not to trivialize development, given the amount of logging Zwift already does here as evidenced by their own details in the above cases, it would be a trivial development effort to simply write/transmit this extra power data behind the scenes for verification. This is not hard stuff – so much so that every trainer and power meter company in the space has tools that do this sort of dual-recording for their own internal development purposes. But in this case – Zwift even has the darn menus already built for it. And they do about 90% of the work in the log files today already.

Zwift could add a bit more logic to validate there are two distinct sources based on manuf ID’s/GUID’s, plus ANT+/BLE ID’s/GUID’s. And they could require the racer have both connected and live before they pass under the starting banner. Without it, the racer simply doesn’t get to race.

Plus, it’s not as if we’re putting all the eggs in one basket, since Zwift already states that if Zwift’s network connection disconnects, per the rules the athlete gets DQ’d anyway (after 1 minute of lack of data connectivity), at all. In fact, this de-baskets the eggs. It means there’s two power sources that could be used as a safety net for the rider/race for any short or transient trainer/power meter connectivity issues.

Now like most questions around Zwift’s aging legacy infrastructure, a fix is always around the corner. In this case they additionally noted that with Zwift’s recent investment round raising $450M, that some of that money was going to revamping older infrastructure issues. And in particular, making these sorts of scenarios cleaner/easier for end users. But ultimately, there’s no clear answer on why this is as complicated as it is.

And even more than that, this would have tremendous benefits to the larger Zwift community of racers, allowing Zwift (and to an extension ZwiftPower) to validate results more accurately and instantly without the added uplift of dealing with secondary files. While also potentially minimizing transient connectivity issues. Seems like a no-brainer.

Summary:

Ultimately though, while these two women got themselves in trouble for the coverup more than the crime, I think it also uncovers the complexities that Zwift racing faces. And while there are many ways people can cheat on Zwift, the core of it roughly comes down to three simple things:

A) Is the racer’s weight accurate?

B) Is the rider who they say they are?

C) Is the racer’s power accurate?

The first one has largely been solved via video weigh-ins for pro riders (though is a dumpster fire for non-pro riders). The second one is solved in pro races via webcams and Zoom already. Whereas the third one could be easily mostly mitigated with real-time dual-power source verification. There’s no reason a rider should even be allowed to pass the start line unless the trainer and power meter are both paired, active, and transmitting different as expected. And there’s a massive number of things Zwift can do around technically validating that (as they’ve shown they’re already doing after the fact).

Of course – it’d also be easier to simply have accurate trainers or power meters. Today Zwift largely forces their pros to use the trainer power as the source for power data in a race instead of a power meter, a somewhat bizarre stance since overwhelmingly power meters made in the last 3-5 years are more accurate than trainers made in the last 3-5 years.

Still, that aside, Zwift says they’re working with the UCI to define ways to have an accurate trainer. Though, based on my conversations with various parties that have been part of that committee – the various parties are a long, long, long way away from agreeing on an even approach, let alone how to implement it. After all, the reality of that decision will ultimately make official what myself and others do on a weekly basis: Show how inaccurate many of the trainers being used are. Which in turn, will make brands unhappy.

And if there’s one thing more intertwined in cycling than cheating…it’s sponsorship.

With that – thanks for reading!

FOUND THIS POST USEFUL? SUPPORT THE SITE!

Hopefully, you found this post useful. The website is really a labor of love, so please consider becoming a DC RAINMAKER Supporter. This gets you an ad-free experience, and access to our (mostly) bi-monthly behind-the-scenes video series of “Shed Talkin’”.

Support DCRainMaker - Shop on Amazon

Otherwise, perhaps consider using the below link if shopping on Amazon. As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. It doesn’t cost you anything extra, but your purchases help support this website a lot. It could simply be buying toilet paper, or this pizza oven we use and love.